The Future of the 15-Minute City

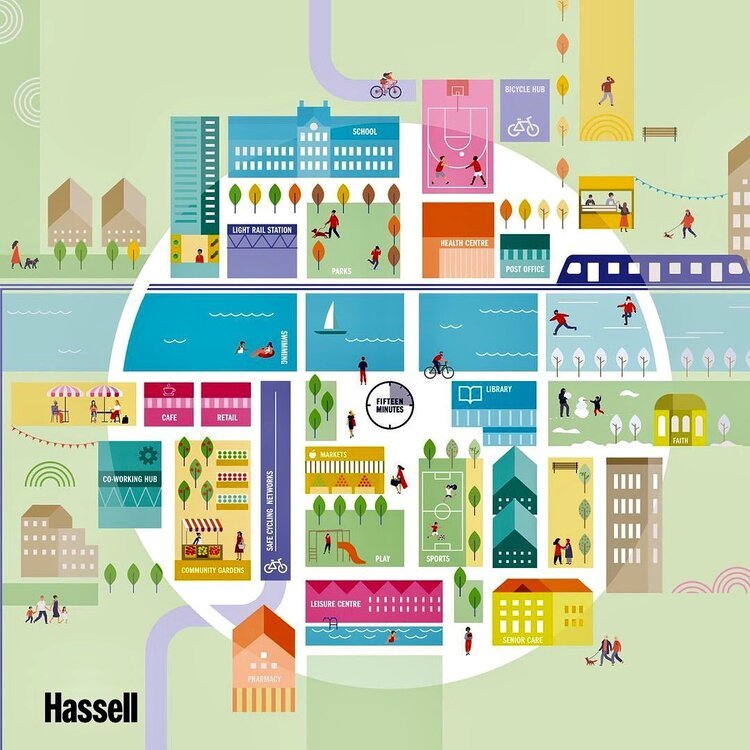

The concept of the 15-minute city is simple: residents can go to work, do their shopping, socialise with their friends, and see their doctor within a 15-minute commute by foot, bike, or public transport. A car-free community, with everything one might need nearby, is not only an attempt to help combat climate change, but also to find an answer to the ever-growing globalisation.

Although the term was coined relatively recently (it was introduced in 2016 by urbanist Carlos Moreno), the ideas behind the 15-minute city have existed in urbanism for decades. Chrono-urbanism, walkability, neighbourhood units, (hyper)proximity, and mixed-use zoning are just some of the examples.

Living in a big city is exciting, hectic, but also environmentally unfriendly, with high rates of CO2 emissions and energy consumption. The concept of having everything within 15 minutes from one’s home, reachable on foot, by bike, or via public transport, would change that. Include the environmental benefits of shopping locally and the growing number of people working from home, and the appeal becomes even clearer.

Urbanist Alain Bertaud conceptualises cities as labour markets. It is true that historically most cities grew from centres of trade and business, building infrastructure to make conditions for labour more practical and productive. In the 19th century, Scottish polymath Sir Patrick Geddes argued that the city must develop with the aim of preserving the social, individual, and civic lives of its inhabitants. That is, to move away from a purely quantitative, wage-centred, and individualistic development which it had fallen into over the centuries. He called this the “eutopia”, a combination of “folk, work, and place.”

Similarly, the 15-minute city is attempting to put the home at the centre of the city.

The concept was popularised by Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo, who embraced Moreno’s idea during her 2020 re-election campaign. Her plan: giving Paris and its neighbourhoods “proximity, diversity, density and ubiquity”, reducing car traffic, and opening up the possibilities in each corner of the city of 2 million (12 million if you count the wider region).

An unfortunate and unexpected occasion to test the idea came in March 2020, when France went into lockdown. Suddenly, millions of people in Paris could only go a kilometre from their homes, which translated to around a 15-minute walk. As a result, Parisians, like many people across the world, spent more time discovering their local shops and communities, which, according to Moreno himself, they might not have done otherwise.

Apart from Paris, plans to bring 15-minute enclaves to life have been implemented in Melbourne, Scotland, Dublin, and Barcelona, to name a few. Saudi Arabia is planning to build a 170-kilometre-long smart city, named The Line, which is set to house nearly 9 million people, and where everything will be reachable in five minutes of walking. For the C40 Cities initiative, a global city-led network focused on fighting climate change, the 15-minute city needs to be at the centre of the post-Covid city development as a way to improve health and well-being.

Some conservatives claim the 15-minute city is a hoax to “impose climate lockdowns” and forbid residents to move freely as they please. However, a 15-minute city is in reality a way to decentralise and alleviate a city’s climate pressures, decongest traffic, and support the development of local communities. One of its main challenges is to create bonds between neighbourhoods, whilst also developing their self-sufficiency. It doesn’t mean a person must stay in their own neighbourhood for the rest of their lives, but it does attempt to encourage a way of life that is more environmentally conscious and in tune with the rhythm of a quartier.

However, it has also received its fair share of criticisms, and rightly so. For one, most of the analysis is based on European cities, which have followed distinctly separate currents of urban development from most US, and many African and Asian cities over previous centuries. For most Americans in urban areas, a bike ride to work is not only impractical but often outright dangerous. Another obvious question is whether people would be able to find work within 15 minutes of their homes. For many, the answer would most likely be no.

The substantial differences between some neighbourhoods, gentrified and segregated based on ethnicity or income, is another factor which we must consider when dividing a city into 15-minute communities. While residents of some neighbourhoods have all that they need and money to invest, others lack the bare necessities and don’t have sufficient funds to spare.

Whilst it has its flaws, it does offer a human-centred perspective on urban development, prioritising the importance of the individual and their relationship with their surroundings. When implemented, it must take into account the unique issues that each city and neighbourhood face. Like any strategy which aims to improve the lives of people, it requires consistent adaptation and development.

So, has the 15-minute city had its fifteen minutes of fame, or is it here to stay? Time will tell whether more cities will try to build their own quarter-hour communities.

And who knows, maybe we will all be living in “eutopias” one day.

Mia Uremović (she/her)

Ecosprinter Editorial Board Member